Ch. 13 - Balance Billing and Fair Coverage

RJ Sontag, MD; Jasmeet Dhaliwal, MD, MPH, MBA; Michael A. Granovsky, MD, CPC, FACEP

Emergency medicine sits at the intersection of the failure of access, coverage, and payment in the modern health system. Under EMTALA requirements, care must be provided regardless of insurance or payment. Without a mechanism to negotiate fair contracts in the setting of mandates to provide care, providers and patients can be left with the problem of balance billing when coverage is not fair or adequate.

Emergency physicians have an ethical and legal obligation to treat all patients, and their engagement in the conversation regarding coverage and payment is more vital than ever.

Balance Billing Defined

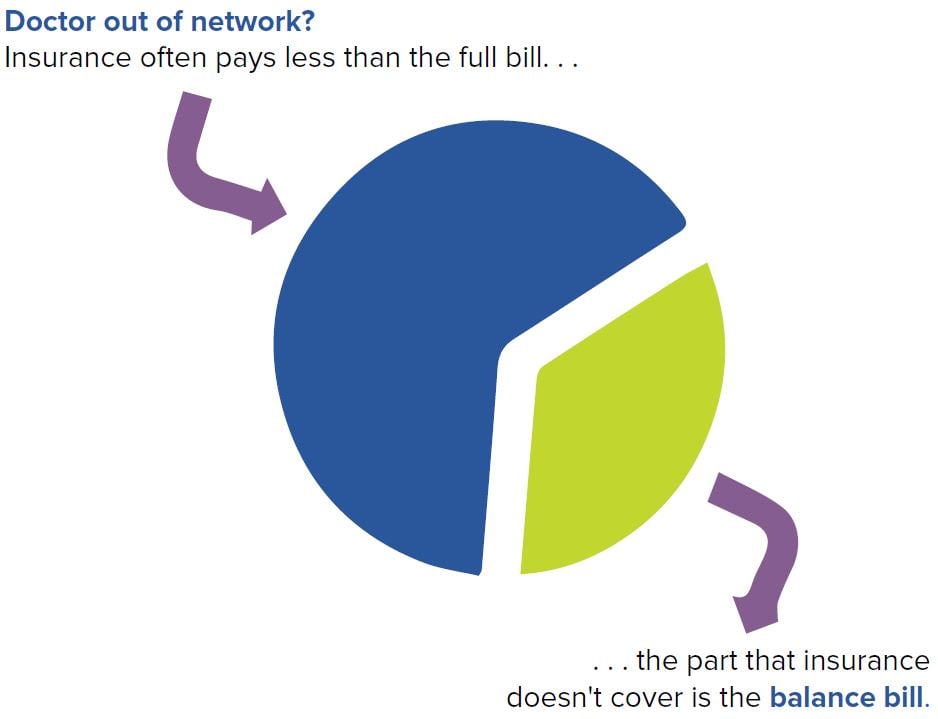

Medical emergencies can be one of the most frightening moments of a person’s life. When faced with a problem like uncontrolled bleeding, chest pain, or a stroke, patients often seek treatment from a nearby ED. After a patient has been treated and stabilized, the physician then bills the patient’s health insurance company. If the provider is “in network,” meaning they have a preexisting contract to provide medical services at a specific rate, the insurance company pays the allowed amount and the patient pays the applicable co-pay, co-insurance, and deductibles. If the provider and health insurance company do not have a contract, the services are “out-of-network” (OON), and insurance companies often pay a lower rate than the physician’s typical charge. To be paid for the treatment in full, the physician who provided the legally required emergency care sends the patient a bill covering the difference between the provider’s billed rate and the insurance company’s paid amount. The provider and patient are often then left to work directly together to resolve the portion of the bill the insurance company would not pay. This practice is known as balance billing.

Figure 13-1. Balance Billing

Scope of Balance Billing

Balance billing burdens all medical specialties, but emergency care is the only care required by law to be provided regardless of insurance status.1 Further, patients do not plan to have a medical emergency, and when time is of the essence they often do not know which emergency physicians are in network or out of network — much less whether a provider working at an in-network ED is employed by that ED or by an out-of-network group. As would be expected, emergency medicine accounts for about one quarter of cases of balance billing.2 While the percentage is not insignificant, the prevalence of balance billing as a total of all ED encounters may actually be as low as 2%.3

When patients do not understand their insurance coverage and the implications of OON care, they can be caught off guard by these balance bills. Further complicating the matter is the increased medical costs related to changes in insurance coverage. HDHPs increase out-of-pocket costs for patients in the form of rising deductibles and copays.4 All of these changes — balance bills, high deductibles, and increased copays — are often lumped together in the media and labeled as “surprise bills.”5 What patients view as surprise bills are actually the result of insurance companies narrowing their networks and increasing costs to patients.

Emergency physicians serve an important role in the health care system by acting as the health care safety net for patients regardless of their insurance status. Like all physicians, emergency physicians believe they should be reimbursed fairly for the care they provide. Unlike other specialties, emergency physicians do not turn away patients based on their ability to pay resulting in our specialty providing the most uncompensated EMTALA-related care.6 Accordingly, ensuring fair payment from insurance companies is of particular importance to emergency physicians. Without the ability to decline contracting and services as other providers do when they are out-of-network, balance billing may be one of the few mechanisms by which emergency medicine can obtain fair payment.

Defining a Fair Rate

Determining a fair rate for emergency medical services is much more complicated than a simple flat fee across the country. Facilities treating uninsured and underinsured (eg, Medicaid) patients have to offset their losses by charging insured patients more, a practice called cost-shifting. The geographical location, cost of labor, taxes and regulatory costs, and other overhead of providing emergency care may further influence the difference in charges between EDs.

To help determine a fair rate, a system exists to analyze the usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) charges for emergency services in any particular geographical region. Based on authority granted to them by the ACA,7 HHS requires insurance companies to reimburse OON emergency services for the UCR charge, unless a greater rate exists in either the typical in-network rate or the typical Medicare rate. Both in-network rates and Medicare rates are substantially lower than the actual cost of care, which would be expected for any negotiated contract. The rule requiring payment at one of these three levels, known as the “greatest of three” rule, then relies on the UCR being fairly determined.8 The federal government is not the only entity requiring reimbursement at those levels. In 2016, Connecticut started requiring emergency services to be provided to patients with costs and reimbursements akin to the greatest of three rule.

The challenge for UCR is the calculation of that rate and whose database is utilized. Insurance companies compile databases of all regions of the U.S. and set their rates based on those averages. They do this privately and are not obligated to reveal their data or methods. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this secretive “black box” method can result in fraud. Prior to 2009, the majority of insurance companies determined their out-of-network UCR charges by utilizing large national databases owned by Ingenix, a subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group. When they were caught manipulating UCR data by more than 30%, United Healthcare paid more than $350 million in settlement.9 They are not alone in covering up the true costs of health care: Aetna attempted to increase their profits with similar manipulation, and in 2012 they had to pay $120 million.10

The settlement funds allowed for the creation of an open-access database to serve as a repository of physician charges. The nonprofit agency overseeing the data, FAIR Health, manages this transparent database and allows for access to actual UCR charges, free of the conflict-of-interest from insurance companies.11

The Greatest of Three Lawsuit

Despite the transparent database creation, insurance companies continue to rely on their own opaque methods for cost determination, and no national rule requires them to use FAIR Health. This lack of transparency violates the ACA’s requirement that OON billers be reimbursed at a reasonable, objective rate. After the ACA was enacted, HHS was tasked with determining if the insurance companies’ method for determining the UCR was lawful. During the rulemaking process, ACEP questioned the objectivity of the insurance companies’ methods and noted that a database like FAIR Health should be used instead. Federal law requires that all comments submitted during the rulemaking period be addressed by HHS, but the department failed to respond to ACEP’s comments, despite their legal obligation to do so.

When HHS finalized the rules without responding to ACEP’s comments, ACEP sued. ACEP contended HHS ignored numerous comments and feedback provided by ACEP and patient advocacy groups. ACEP prevailed, and HHS was forced to respond to those public concerns.12 By 2018, the courts had yet to determine if the response from HHS was sufficient.

ACEP’s lawsuit also contended that insurance companies have an inherent conflict of interest in using their own secretive databases. By 2018, the courts had not yet ruled on ACEP’s substantive claims regarding the lack of transparency involved in the determination of the UCR standard.13

Legislative Solutions

Patients reasonably expect their health insurance to cover their emergency care. Balance billing pits patients and physicians against each other when the problem lies in insurance coverage. As expected, consumer advocacy groups and federal and state legislatures are stepping up to find solutions.14 These policies have found a home in federal and state laws over the past decade, closing some of the gaps, but leaving the need for a more comprehensive solution.15 Some solutions are imperfect, like the one described above wherein

the federal government and states like Connecticut apply the greatest of three law erroneously. Solutions often require addressing minimum benefit standards, balance bill caps, dispute resolution, informed consent, and network adequacy.

Minimum Benefit Standard. When a balance bill occurs, most parties want it resolved with minimal administrative cost and a standard minimum payment is often sought in statute. The challenge is agreeing to what that amount is tied to, as insurers and providers are often on opposite sides of the issue. Providers want either billed charges or a database that uses a reasonable payment standard (eg, FAIR Health). Insurers want the lowest amount possible, and they advocate for Medicare rates. Both sides are concerned that a rate above the current marketplace will drive costs and payments up if too high or down if too low.

Balance Bill Caps. One solution proposes legal regulations to prohibit or limit the amount of the balance bill, which provides a certain amount of protection to patients. States like Texas and New York pioneered this policy solution of limiting balance billing. As with the policy requiring reimbursements, this solution is not without flaws. For many patients, the balance bill limit ($500 in Texas, for example) is not an insignificant expense. At the same time, the actual bill may be substantially higher, leaving the physicians who are legally required to provide medical care without a legal guarantee to payment for that care.

Dispute Resolution. Appeals are possible when a balance bill is above a state cap or threshold in some states. Texas provides for a mediation process for higher bills, and New York provides for a binding arbitration process. As with the aforementioned required reimbursements, these policies apply differently to different types of insurance, leaving many patients and physicians without a solution.16,17 There is also concern about the cost of dispute resolution over a small bill. If a provider is required to pay $1,000 for arbitration for a $250 bill, there is no economic incentive unless multiple claims can be bundled. The ability to bundle like claims has complicated many dispute resolution processes with some states, such as California, permitting it.18 Other states, like Connecticut, have not taken a position on the issue or not permitted it.19

Disclosure and Consent. Some states require disclosure in advance so a patient can make an informed decision about whether to accept out-of-network care.20 This solution makes sense for non-emergent care when there is time to research in-network physician options. In medical emergencies, the luxury of time rarely exists, meaning advanced disclosure is of limited value and ability. Further, EMTALA prohibits emergency departments from disclosing whether their services are OON until after the care has been provided.21 Other states have required websites and lists of included insurance products to be maintained, which can introduce new administrative costs and challenges for practices.

Network Adequacy. Many legislators and regulators are bothered that a hospital can be in-network, while the providers working there can be OON. Further, entire communities can have multiple major hospitals without a single in-network provider. As a result, ensuring that networks are adequately staffed by both hospitals and providers has come into the discussion of balance billing. In one example, the Texas Department of Insurance has a network adequacy requirement that requires contracted providers be available at contracted hospitals within a specified distance for the patient. Despite the legal requirement, not all insurers comply. In a 2018 settlement, Humana was fined $700,000 for network inadequacy and had to process previously out-of-network bills as in-network.22

First-Dollar Coverage. First-dollar coverage — the concept that insurance plans allow for certain types of care by providing 100% coverage from the first dollar spent toward that care — presents an additional path toward eliminating balance billing of patients.23 First-dollar coverage models allow for a predetermined copay for care (or no co-pay at all), with the remainder of the bill being paid by the insurance company.24 These plans eliminate the patient’s deductible, which is a significant reduction in modern plans, particularly high-deductible plans. Such coverage would allow patients to access emergency care as described by EMTALA without being subject to balance billing by physician.

Model Legislation. Model legislation now exists that looks to strike a balanced solution to this problem. The Physicians for Fair Coverage have proposed a comprehensive solution that prohibits punishing patients for unexpected OON bills. This is accomplished by both prohibiting insurance companies from charging OON fees to patients for these visits and stopping physicians from directly billing patients. They recommend linking fair charges to an open, independent database, such as FAIR Health, and they recommend eliminating the ability of insurers to provide confusing and misleading information regarding coverage. By designing this model legislation, Physicians for Fair Coverage hope to provide a path for patients, insurers, physicians, and legislators unite behind a uniform, fair solution to the problems that create the need for balance billing.25

WHAT’S THE ASK?

Balance billing and denials of coverage affect patients’ ability to seek appropriate care and threatens the ability of emergency physicians to provide that care. Emergency physicians have an ethical and legal obligation to treat all patients, and their engagement in the conversation regarding solutions is more vital than ever. Advocacy can include:

- Advocating for fair solutions to the current reimbursement challenges.

- Discussing with your elected officials how regulations are impacting your patients and your practice.

- Supporting the organizations fighting detrimental policies.

- Recruiting your peers as fellow advocates.