Ch 23 - Palliative and End-of-Life Care in the ED

Jason K. Bowman, MD; Chadd K. Kraus, DO, DrPH, MPH, FACEP

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.”1

It is critically important to address goals of care with patients in the ED, particularly those with lifelimiting illnesses, and not assume that their outpatient providers have done this.

The field of palliative care has evolved into a formalized medical specialty that focuses on optimizing patients’ quality of life throughout the illness spectrum (particularly in life-limiting illness) by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering of all kinds. Hospice care is closely related, and usually defined as care and symptom management provided to patients in the last 6 months of life.

Emergency Medicine and Palliative Care

In 2012, ACEP released a white paper outlining the unique aspects of palliative and hospice care in the ED.2 Emergency physicians frequently care for patients with life-threatening and life-limiting illnesses and injuries. One study estimates that 75% of older adults visit the ED in the last 6 months of life.3 However, endof-life conversations with a patient’s primary care physicians and outpatient specialists are often postponed,4,5 leaving those discussions to emergency physicians. A recent RAND study suggested that primary care physicians and specialists increasingly rely on EDs to evaluate complex patients with potentially serious health problems, rather than managing these patients themselves.6 These utilization trends and patient complexity make the ED an appropriate and increasingly important setting for meeting the palliative care needs of patients with a broad range of advanced, chronic, and/or life-limiting illnesses.7-20

There are multiple challenges to providing palliative and end-of-life care in the ED, including a paucity of hospice and palliative subspecialists for consultation, time constraints, management of multiple patients, and the lack of a longterm physician-patient relationship between emergency physicians and their patients.11-20 As such, it is especially important for emergency physicians to have basic palliative care skills.11,21 In order to help equip emergency physicians with these skills, the Improving Palliative Care in Emergency Medicine (IPAL-EM) initiative of the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CPAC) “offers a central portal for sharing essential expertise, evidence, tools and practical resources to assist clinicians and administrators with the successful integration of palliative care and emergency medicine.”22,23

Integrating palliative care into the ED setting is becoming increasingly common, especially for specific groups of patients with palliative care needs, such as patients with dementia24 and patients with cancer.25,26 With the rise of geriatricspecific emergency care, incorporating ways to identify patients with palliative and/or hospice needs, even as early as in triage, has become a way to provide expedient palliative care.27-31 ACEP developed a Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program to “ensure that older patients receive well-coordinated, quality care at the appropriate level at every ED encounter.”32

When hospice and palliative care specialists are available, the ED is an appropriate setting for initiating palliative care consults.33-37 In its initial Choosing Wisely recommendations, ACEP highlighted the importance of palliative and end-of-life care in the ED, by addressing it among their 5 recommendations: “Don’t delay in engaging available palliative and hospice services in the emergency department for patients likely to benefit.”38 Early palliative and hospice services can benefit patients and families by ensuring the patient’s goals of care are respected and followed, and potentially reducing unwanted or unnecessary care at the end of life. Patients who receive timely palliative and hospice services might have improved quality of life and potentially longer life expectancy.34,36,37

Palliative care initiated in the ED offers the opportunity for patients to experience symptom relief, to obtain referrals to community resources and home services, and, when appropriate, to avoid hospitalization.7,17,34,39,40

Advance Planning Documents

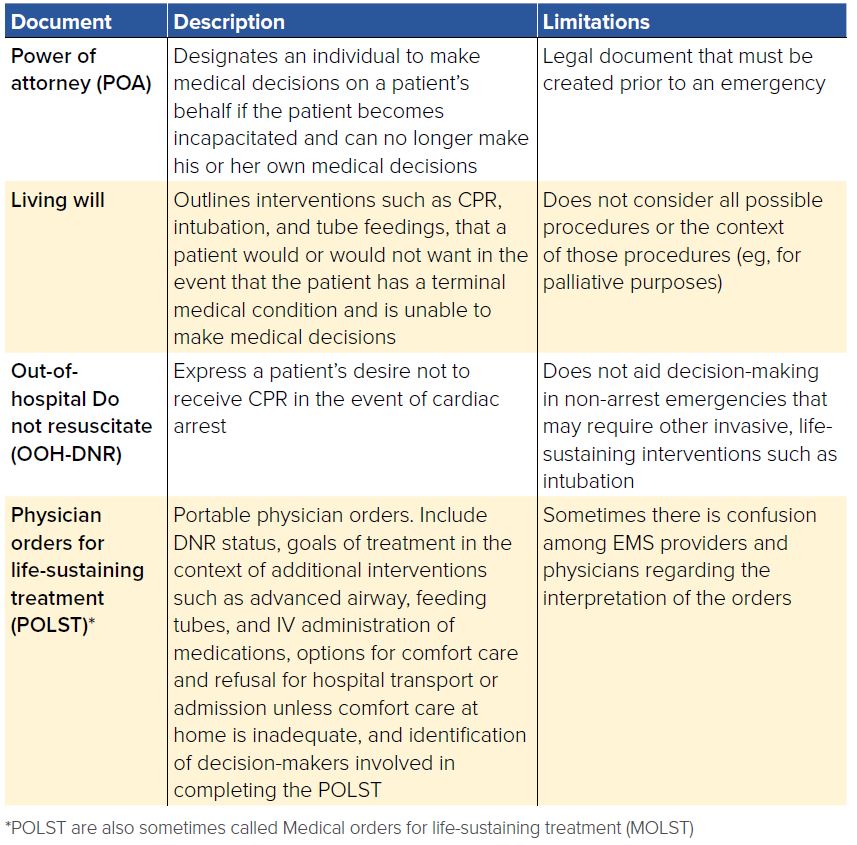

In 2014, the Institute of Medicine released a report on end-of-life care in America, “Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life.” A key recommendation of this report is to “improve delivery of end-of-life care to one that is seamless, high-quality, integrated, patient-centered, family-oriented, and consistently accessible.”41 A focus area in order to meet this goal is improved clinician-patient communication for advance care planning. Advance care planning can take a variety of forms and can be represented in a range of documents and directives that can help guide clinical decisions in a patient-centered way that respects the patient’s goals and values. (Table 23.1)

TABLE 23.1. Advance Planning Documents

Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) are a set of portable medical orders that have become a critical component of advance care planning relevant to patients expected to be in their final year of life. Introduced in Oregon in 1991, POLSTs fill an important gap left by other advance directive documents. POLST forms are dynamic, with revisions as appropriate to changes in health status or patient goals, often as patients near the end of life.42 As a physician’s order, POLSTs are potentially an improvement over traditional advance directives.43 While the patient maintains decision-making capacity, he (or his surrogate decision-maker upon his incapacity) can choose to overturn the POLST decision during a medical emergency.

As of April 2018, the National POLST Paradigm has classified POLST programs by state/territories into “mature” (3 states), “endorsed” (23 states), “developing” (24 states), and “not conforming” (4 states).44 POLST forms impact treatment in the out-of-hospital settings by providing EMS with physician orders that are clear instructions about patient preferences and enabling greater individualization of care during out-of-hospital emergencies.45-48

Despite the growing use of POLST forms, there is frequently confusion among EMS providers and emergency physicians regarding the interpretation of the orders, suggesting the need for additional research, education, training, and safety efforts to ensure that the patient’s goals and values are being carried out in treatment decisions.49-51

One limitation of advance planning documents for end-of-life and palliative care decision-making is that these documents might not consider or list the many possible interventions during critical illnesses or account for the dynamic nature of an illness. For example, they might not address the possibility of intubation to facilitate a palliative surgery performed to reduce the pain caused by a large tumor. The definition of a terminal condition is also difficult to identify. Thus, these documents often are more of a starting place for a conversation with patients, rather than a prescription to be followed without consideration for changing situations.

Medico-Legal and Ethical Considerations

Emergency physicians have an ethical obligation to honor a patient’s values and goals of care while providing quality care as indicated. For patients with palliative and end-of-life care needs who present to the emergency department, there are multiple medico-legal issues to consider. As with any patient presenting to the ED, EMTALA requires that patients with palliative or hospice care needs receive a medical screening exam to determine if an emergency medical condition, including uncontrolled pain, exists. If such a

condition exists, then further evaluation and treatment should be based on a patient’s values and goals, as expressed by the patient or a surrogate, or as outlined in an advance care planning document such as an advance directive, living will, OOH DNR, or POLST.

In many cases, patients with expressed wishes against aggressive treatments still require treatment for pain or other symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, and may even need admission to an ICU.52 There is a risk of incorrectly assuming that a patient who does not want aggressive interventions does not require care. Rather, patients with palliative and end-of-life needs still should receive the best, intense, expert possible — but guided by and consistent with their goals and as outlined by them, family, and/or in their advanced care planning documents.

A patient with decision-making capacity retains his/her right to override the goals and values codified in these documents at any time. A legal designee (including a family member) who is identified by a living will/advance directive or a POLST cannot make changes to a patient’s stated goals or wishes if the patient has decision-making capacity. It is critically important for EMS and emergency physicians to act with a patient-centered focus based on legal and medical documents and not to act solely on family-reported goals and values. When doubt exists about providing treatment, unless there is a documented patient wish for specific goals and values, providers should assume full care and resuscitation.

When there are issues about end-of-life care and the patient is incapacitated, it is important for emergency physicians to understand the surrogacy laws and regulations in their state.53 After a patient is incapacitated, each state has a statute governing the order in which decision-maker(s) is/are appointed. In most cases, a court-appointed guardian, followed by any legal power of attorney has medical decision-making responsibility, although many patients will not have either of these. The next surrogate decision-makers are a spouse, adult children, parent, and then brothers or sisters of the patient. Because the designees represent the goals and values of the patient, they have the authority to change any documents such as DNR and POLST forms.

Current Issues and Future Directions

Broader public and legislative discussions of these topics are likely to impact ED care in the future. Since 2015, Medicare has reimbursed providers for having goals of care conversations with patients.54 However, further efforts are needed to ensure these goals of care conversations occur (and are appropriately documented) more uniformly. Currently, national completion rates for advance directives are just over one-third of all adults.55 Thus, it is critically important to address goals of care with patients in the ED, particularly those with life-limiting illnesses, and not assume that their outpatient providers have done this. While the chaotic environment of the ED is not ideal for such conversations, doing otherwise risks violating patient autonomy and causing harm.

In addition to the growing importance of palliative and end-of-life care in the ED, there are larger movements that have brought palliative and hospice care into the public consciousness and have fueled controversy around decisions made by and for patients near the end-of-life. One example of this controversy is physicianassisted dying, which, as of June 2018, was legal in 6 states: Oregon, Washington, Vermont, Montana, New Mexico, California, and the District of Columbia.55 The exact role of emergency physicians with regard to physician-assisted dying in states where laws exist is yet to be determined, although emergency physicians could conceivably care for patients who have chosen this route.

For emergency physicians, the opioid epidemic has important implications for palliative care provided in the ED. According to the HHS using data from 2016 and 2017, an estimated 2.1 million Americans have an opioid use disorder, leading to approximately 42,000 deaths annually.57 Patients with cancer-related pain are also at risk for opioid misuse, with one study estimating that nearly one-third of patients with cancer presenting to the ED of a comprehensive cancer center were at high risk of opioid misuse.58 Many patients with life-limiting illnesses often do not receive adequate symptom management and experience intense suffering.59 Balancing effective pain management with the iatrogenic risk of harm from opioids is a complex challenge, and an area of intense research and discussion currently within palliative care.

Finally, while the rate of deaths occurring in the ED dropped by nearly half between 1997 to 2011,60 deaths still occur frequently in the ED. Most current providers received no formal training in residency on how to care for the imminently dying patient (and their loved ones) in the ED, or on primary palliative care skills.21 However, recent research suggests that such training is beginning to be incorporated into residency training.21 Understanding how to provide appropriate, intensive symptomatic and supportive care is a critical skill for emergency physicians. Equally important is the fundamental role played by emergency physicians in advocating with legislators, regulators, and other stakeholders to advance appropriate care for patients with palliative needs in the ED. This advocacy is necessary across the spectrum of topics, from education about and promotion of POLSTs, to ensuring adequate reimbursement for palliative care provided in the ED.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- • Advocate for inclusion of primary palliative care skills into EM residency training programs.

- • Advocate for broader adoption of POLST and related forms and to improve EMS/emergency physician education and training on how to apply POLST.

- • Advocate for the continued recognition of the value of and reimbursement for palliative care services in the ED.

RESOURCES

- • ACEP Palliative Care Section https://www.acep.org/how-we-serve/sections/palliative-medicine

- • AAHPM EM Special Interest Group (SIG) http://aahpm.org/uploads/List_of_AAHPM__HPNA_SIGs_Final.pdf

- • Emergency Medicine Resident Palliative Interest Group (ACEP + AAHPM) https://goo.gl/forms/uw9m58H1DVr8XWbY2

- • EMRA Palliative Care Sub-Committee https://www.emra.org/be-involved/committees/critical-care-committee