Ch. 19 - Medical Liability Reform

Aya Itani, MD, MPH; Cedric Dark, MD, MPH, FACEP

A medical malpractice lawsuit presents an overwhelming emotional, financial, and reputational risk to a physician. The impact of medical liability is massive; in fact, 99% of physicians in high-risk specialties by age 65 years old have already been subject to a claim, and approximately 7% of emergency physicians are sued each year.1

Emergency medicine is a high-risk specialty for medical malpractice, with 1 out of every 14 emergency physicians getting sued each year.

The medical malpractice environment affects workforce availabilities to underserved areas and is therefore a concern to those interested in health equity and patient access to care. Moreover, physicians are torn between the competing interests of minimizing health care costs for patients (and for the overall health care system) and minimizing their own liability by practicing defensive medicine (by ordering unnecessary diagnostic tests or opting out of service to higher-acuity patients).Threatened by the rising price of liability insurance and the negative impact on patient access to care, physicians advocated for legislative action to secure a balanced medical malpractice environment. These advocacy efforts eventually gave rise to “tort reform” in several states: legislative changes to state laws governing medical liability.3 Medical liability reform has been crucial for controlling burdensome rising malpractice premiums.4

Medical Malpractice Basics

State Laws

The framework that governs medical malpractice is established under the authority of individual state laws (unless overruled by a higher state court). Thus, medical malpractice law varies across different jurisdictions from state to state.

Basic Elements of a Claim

According to medical malpractice law, the injured patient — the plaintiff — must prove 4 elements to have a successful malpractice claim:5

- A professional duty owed to the patient

- Breach of such duty in delivering the standard of care

- Causation

- Harm and damages

The professional duty is an assumed understanding and expectation of the provider, who is said to owe a duty of reasonable professional care to the patient. The definition of breach of duty is highly heterogeneous among states, as each state has its own standard of care guidelines and expectations.3 The plaintiff’s injury must be caused by such a breach of care and not explained by other causes. The plaintiff’s attorney must prove that the expenses s/he claims were reasonably necessary and proximately caused by the defendant’s negligence.6

Economic, Noneconomic, and Punitive Damages

Three types of damages can be sought against the defendant in medical malpractice cases. Economic damages include the monetary losses that the plaintiff has incurred, or is likely to incur in the future, including costs of medical care and lost wages. Noneconomic damages include non-monetary losses such as pain and suffering. On rare occasions, punitive damages may be sought if the plaintiff claims the physician practiced with an intent to harm the patient, rather than simple negligence.

State-Enacted Medical Liability Reforms (“Tort Reforms”)

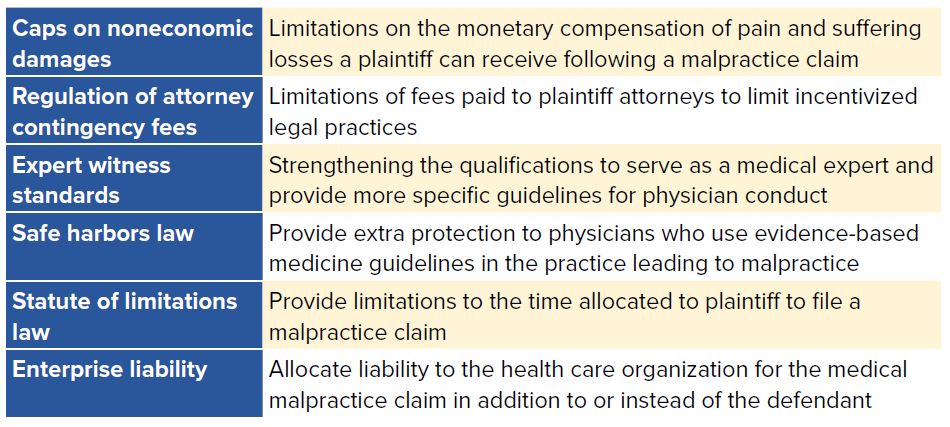

Existing state medical liability reform components can be categorized in the following groups: caps on noneconomic damages, regulation of attorney contingency fees, enhancing expert witness standards, safe harbors, and statute of limitations (Table 19.1).

While some medical liability reform strategies have successfully reduced malpractice payouts and malpractice premiums for physicians, existing data has not shown a decrease in health care utilization by emergency physicians in states where liability reform has been enacted.7

Caps on Non-economic Damages

Caps on non-economic damages place limitations on the monetary compensation a plaintiff can receive following a malpractice claim. In states where they have been enacted (such as Texas, California, Nevada, and Indiana), caps on noneconomic damages have been successful at reducing payments to plaintiffs as well as reducing the cost of malpractice insurance premiums for physicians. The effects of noneconomic damage caps on premiums vary according to the amount of the cap.8 Compared to no cap, a cap of $500,000 did not show a statistically significant reduction in malpractice insurance premiums, while a $250,000 cap successfully reduced malpractice insurance premiums by 20%.

TABLE 19.1. Medical Malpractice Traditional Reforms

Regulation of Attorney Contingency Fees

In the United States, lawyers for aggrieved parties (plaintiffs) are usually hired on a contingency-fee basis, meaning the lawyer gets paid only if a monetary damage is awarded. This system has been criticized as encouraging dishonest behavior by lawyers on behalf of the patient. Our current system discourages the filing of meritorious medical malpractice cases that have either a low chance of monetary recovery, or if money is recovered, a relatively small payout and, similarly, discourages lawyers from taking work-intensive cases unless the possible payout is large.9 Contingency fees apply to both settlements and monetary damages awarded by a court. Some states, such as California, have enacted limits on contingency fees paid to plaintiff attorneys to help remove some of these perverse incentives.

Expert Witness Standards

Under traditional common law evidentiary standards, an expert witness must have the education, training, or experience to testify about a particular issue in a lawsuit. Because of the broad nature of this standard, a medical expert witness in a case does not necessarily need to have actual clinical experience in the same specialty as the defendant physician, nor is it required that their clinical experience is current or in a similar practice setting. Because of these discrepancies, some states have passed legislation specifying stricter

qualifications for expert witnesses in a medical malpractice case.

Physicians serving as expert witnesses have an obligation to present complete and unbiased information to be used by the jury to ascertain whether the defendant was medically negligent and whether, as a result, the plaintiff suffered damages.

The best strategies for improving the quality of medical expert witness testimony are strengthening the qualifications for serving as a medical expert witness and providing more specific guidelines for physician conduct throughout the legal process.10 To serve as an expert witness in emergency medicine, per ACEP guidelines, a physician should be currently licensed as a doctor of medicine or osteopathic medicine, be certified by a recognized certifying body in emergency medicine, and be in the active clinical practice of emergency medicine for at least 3 years (exclusive of training) immediately preceding the date of the case.11

Specific state qualifications for expert witnesses, however, may vary. Two states with favorable expert witness qualifications include West Virginia and Nevada. To qualify as an expert witness in West Virginia, a physician must not only have the appropriate experience in diagnosing or treating injuries similar to those of the plaintiff’s, but also, the physician must have spent at least 60% of his or her professional time in active clinical practice at the time of injury. In Nevada, expert witnesses must be 75% clinically and/or academically active and of the same specialty as the defendant.12

Safe Harbors for Evidence-Based Medicine

Safe harbor laws, advocated by some physicians, would secure an added protection to physicians who use evidence-based guidelines in their practice. While this reform has been argued to improve patient safety by adhering stricter to clinical guidelines, numerous hurdles must be overcome to implement it. Some of these hurdles include building non-physician stakeholder support, obtaining legislative approval, and regularly updating guidelines. Safe harbor policies have been trialed in several states, including Florida, Maryland,

Minnesota, Maine, and Vermont. The Maine program was trialed for 5 years and showed a high rate of physician opt-in, but the guidelines were only used once as a defense in a malpractice case.13

In addition, recent federal proposals for “safe harbor” liability protection have failed to gain traction. In 2014, despite ACEP’s support, H.R. 4106 “Saving Lives, Saving Costs Act” failed to pass. This legislation would have provided increased liability protection in the form of a legal “safe harbor” for physicians who can demonstrate that they followed clinical practice guidelines or best practices developed by a multidisciplinary panel of experts.

Statute of Limitations Law

Statute of limitations laws limit the amount of time the plaintiff has to file a malpractice claim. Many states have a statute of limitations of 2–3 years. In cases where the injury is not immediately apparent, the time period may not start until after the discovery of an injury. When the time for the statute of limitations is decreased, studies have shown a modest decrease in malpractice insurance premium growth but no significant change in malpractice payments.

Specific State Examples and Federal Response

States have adopted varying medical liability reforms over the past 40 years. In California, the Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act (MICRA) passed in 1975, capping noneconomic damages at $250,000 and limiting plaintiffs’ attorneys’ contingency fees. California’s law is credited with slowing the growth of malpractice premiums in the state and has reduced the amount awarded to plaintiffs there.14 While proponents argue that it has improved access to care and kept health care costs down,14 detractors argue that injured patients are now unable to find lawyers and that changes in access to care and cost cannot be attributed to MICRA.15

In 2003, the Texas Legislature made significant changes to the Medical Liability and Insurance Improvement Act (MLIIA) that led to an improved medical liability environment; these include $250,000 cap on noneconomic damages, stricter expert witness standards, and a statute of limitations of 2 years for malpractice claims.16 A provision specific to emergency care raised the burden of proof in emergency cases to “willful and wanton negligence.” As a result of these reforms, Texas has one of the most EM-friendly medical malpractice environments in the country, with low malpractice premiums and low payouts when malpractice cases occur.17

Federal proposals to enact medical liability reforms have largely failed to gain significant traction. President Bill Clinton’s proposals to cap noneconomic damages and institute alternative dispute resolution forums in 1993 were dropped in the wake of opposition by physicians and managed care organizations. President George W. Bush’s comprehensive federal tort reform legislation, which included a national cap on non-economic damages, failed to pass in 2005.

The Health Care Safety Net Enhancement Act (H.R. 548/S. 527 in the 2017 legislative session) would provide liability protection to physicians practicing under the EMTALA mandate as if they were federal employees acting on behalf of the Public Health Service. This protection ceases once patients are determined not to have an emergency medical condition or patients have been stabilized. Also, the legislation would extend the same legal protections that Congress had already extended to employees of community health centers and free clinics to physicians who care for patients with emergency medical conditions. ACEP supports this legislation, as it has the potential to protect access to emergency care while reducing the cost of defensive medicine.

The Protecting Access to Care Act (H.R. 1215 in the 2017 legislative session) was a package of proposed medical liability reforms that included limits on statute of limitations, a $250,000 cap on noneconomic damages, and limits on attorney contingency fees. This package passed the House of Representatives in June 2017.18 President Trump’s administration has pledged to support this tort reform package, and it is estimated that these reform efforts would reduce health care costs by reducing the practice of defensive medicine.19 According to the Congressional Budget Office, implementing the package of reforms would result in a 0.4% decrease in health care costs, resulting in a decrease of federal health expenditure of $14 billion over the first 5 years of implementation.20 Neither of these bills were passed into law in the 2017 legislative session, but both are important examples of recent federal efforts to reform the U.S. medical liability system.

Understanding the Limitations

Most medical liability reform has been focused on reducing malpractice premiums and alleviating the financial burden on health care providers. While existing state-based reforms have been successful at reducing the economic burden on providers, they have failed to reduce the overall emotional cost of medical malpractice lawsuits on physicians and have not clearly benefited society by reducing health care costs.12 Consequently, the focus on improving the medical liability milieu is shifting toward improving the health care system

overall: focusing on improving quality, reducing cost, and increasing equitable access. The climate surrounding medical liability differs between states, which allows physicians to distribute themselves based on many factors, one of which is a favorable medical liability milieu — a fact policy makers should note.5

Emergency medicine is a high-risk specialty for medical malpractice, with 1 out of every 14 emergency physicians getting sued each year.1 Empirical evidence demonstrates that tort reforms, such as caps on non-economic damages and reduction of the statute of limitations, will reduce the cost of malpractice insurance premiums. Some states have seen tremendous benefits by implementing these reforms. An opportunity exists to renew efforts to pass federal legislation providing special protections for care provided under the

EMTALA mandate as the political climate continues to change during future Congressional sessions.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

- Advocate for improvements in the malpractice environment in your state with sensible potential solutions such as caps on noneconomic damages, limits on attorney contingency fees, expert witness standards, and reducing time allowed to file a malpractice complaint.

- Advocate for malpractice liability reforms that control health care costs, ensure patient safety, and improve quality of care overall.