Ch. 7 - Frequent Fliers: High Cost, High Need

Hannah Gordon, MPH; Marisa K. Dowling, MD, MPP; Theresa E. Tassey, MD, MPH; Aaran Brooke Drake, MD

Frequent fliers, super-users, or high utilizers — terms used interchangeably — are individuals who visit the ED repeatedly, accounting for a disproportionate share of ED visits, taxing health care resources. Given the ED’s role as the backbone of America’s health care safety net, how can these patients be better served in our emergency care system?

Afflicted by limited or poorly coordinated primary care, chronic and psychiatric diseases, and a variety of socioeconomic factors, high utilizers face an uphill battle in managing their health.

Defining High Utilizers

The highly scrutinized group of ED patients known as high utilizers sparks considerable debate in provider and policy circles. The definition of “high utilizer” varies, but 4 or more ED visits per year is the most common threshold. Others define high utilizers as those who visit the ED beyond “reasonable use,” have more than one ED visit per year, or who have a number of ED visits greater than the 99th percentile.1

While high utilizers represent a small percentage of the total number of ED patients (4.5–8%), they constitute a disproportionate percentage of annual ED visits (21–28%).1–3 Policymakers and clinicians alike focus on high utilizers because of their significant impact on ED crowding, recidivism, EMS resources, and health care costs.4

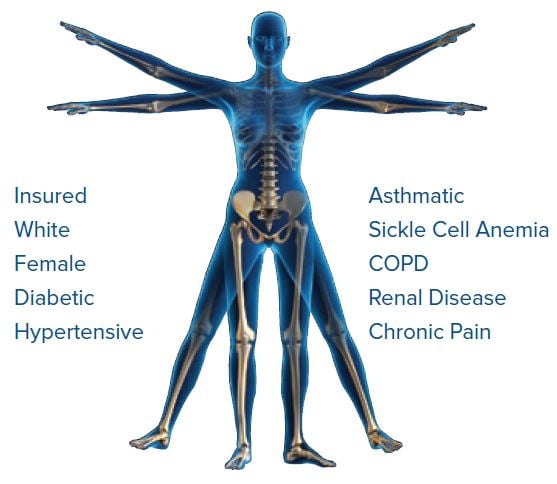

Society often labels the homeless, uninsured, minorities, or those presenting “inappropriately” with non-urgent complaints as high utilizers.1 Research, however, has shown otherwise. High utilizers are more likely to be insured, Caucasian, female, and have chronic medical conditions.5–7 The most common conditions afflicting high utilizers include diabetes, hypertension, sickle cell anemia, asthma, COPD, renal disease, and chronic pain. The high prevalence of chronic disease among high utilizers translates into higher acuity levels at ED triage and more than double the odds of hospital admission and mortality when compared to patients who occasionally visit the ED.1,8 In fact, only about 10% of frequent users’ visits are for clearly non-urgent conditions.9 Similarly, pediatric patients with frequent ED visits have higher rates of mental illness, substance abuse, and chronic disease.1

According to a 2006 study, 84% of high utilizers were insured, with 81% of these having a source of primary care.1,4 Since the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), the percent of patients with health insurance has increased. However, that does not necessarily equate to primary care access.10 Studies indicate that the newly insured and Medicaid patients have higher rates of ED use10 and that frequent ED utilizers also heavily utilize other parts of the health care system, including primary care.11

Moreover, high utilizers are not a static population. Individual patients may experience alternating periods of increased versus decreased ED use. A patient with an exacerbation of a chronic condition (cancer) that then stabilizes (remission) is an example of the intermittent high utilizer.12 Consequently, “one size fits all” solutions for this population often fail.

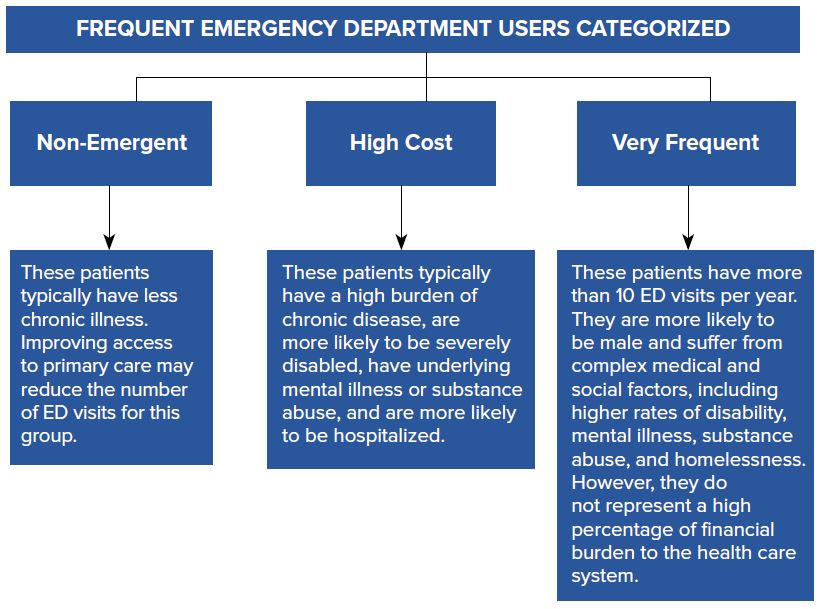

In an attempt to better understand this population, the Congressional Research Service outlined several categories of high utilizers based on their usage patterns, which may point to potential solutions.13

Frequent ED Users

FIGURE 7.1. Anatomy of a Frequent Flier

Frequent non-emergent users — This group includes those with private insurance and a primary care physician, but who may have barriers to accessing primary care resources, leading them to seek care for non-emergent conditions that could be treated in an alternative location. They typically have less chronic illness. Improving access to primary care may help reduce the number of ED visits for this group.

High cost health system users — These patients generally have 4–9 ED visits per year. Patients in this group have a high burden of chronic disease, are more likely to be severely disabled, have underlying mental illness or substance abuse, and more likely to “shop” for providers. Because of their underlying illnesses, this group is the most expensive for the health care system since they are the most likely to require extensive testing and hospitalization following their ED visit.

Very frequent ED users — This group is a small portion (1.7%) of patients with more than 10 ED visits per year.13 They are more likely to be male and suffer from complex medical and social factors, including higher rates of disability, mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness. They are less likely to require hospital admission and thus are less expensive for the health care system.1

FIGURE 7.2. Frequent ED Users Categorized

Utilizing this framework to categorize high utilizers may guide case managers, physicians, and health care centers as well as local, state, and national policymakers in targeting solutions to better serve these individuals’ needs.2,14 Specifically, improving coordination of primary care, augmenting mental health and substance abuse resources, tailoring case management strategies, and removing socioeconomic barriers to primary health care could help decrease the number of ED visits for many of these patients.13

Controversies in the Management of High Utilizers

While providers, patients, and lawmakers want to improve care and access to resources for high utilizers to address their needs, the methods that are proposed can create their own controversies and legal challenges. The requirements of EMTALA and protecting the prudent layperson are two of the challenges most often confronted.

EMTALA

In 1986, Congress passed EMTALA, formalizing the ED’s central role in the U.S. health care safety net — especially for high utilizers.7 While many emergency physicians take pride in the charge to provide care for “anyone, anything, anytime,” this pride can be strained in the case of certain super-users. EMTALA requires that health care providers conduct an MSE for each patient presentation, regardless of how repetitive or non-emergent a particular patient’s complaint may appear. Additionally, some patients may interpret EMTALA to mean that EDs must provide free and all-encompassing health care to all comers, whether the condition is emergent or not, perhaps further driving costly ED use.7,15 The direct cost of uncompensated EMTALA care has been estimated at $4.2 billion.17

Certain federal programs, such as the Medicare and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, exist to assist hospitals in off-setting these costs.7 However, decreasing DSH payments under the ACA could eventually adversely affect EDs that care for a high portion of low income and frequent utilizer patients.18

Prudent Layperson Standard

The prudent layperson standard (PLS) raises another controversy in managing frequent ED utilizers. PLS dictates that ED visits should be reimbursed based on a patient’s symptoms (eg, chest pain), not their final diagnosis (eg, acid reflux).

Despite PLS, in 2017 several insurance companies enacted policies to deny coverage for ED visits based on discharge diagnoses.21 These policies assume that patients (especially high utilizers) are “inappropriately” seeking ED care for low acuity conditions rather than seeking care in less expensive settings. Research has shown this assumption is unfounded. High utilizers, in particular, face barriers to primary care and/or socioeconomic challenges, making the ED at times the only viable option for timely medical care.

Consequently, health insurance policies that deny payment based on ED discharge diagnoses represent a threat to public health, especially for high utilizers with their increased incidence of chronic disease.

How Can We Improve?

The ACA represents a major step toward converting the U.S. health care system from fee-for-service (FFS) (ie, payment based on individual patient encounters) to value-based care. While FFS rewards the volume of services, value-based care reimburses on the premise that higher quality of care and better population health will lead to reduced payer costs. As hospitals have become increasingly penalized for readmissions for certain diagnoses, administrators have turned to patient-centered programs predicated on interdisciplinary team approaches such as case management, individualized care plans, and information sharing. Traditionally, this movement has centered on primary care specialties, rather than emergency medicine. However, several landmark EM-based programs in Maryland, Washington, and California have emerged with impressive results.

Program Overview

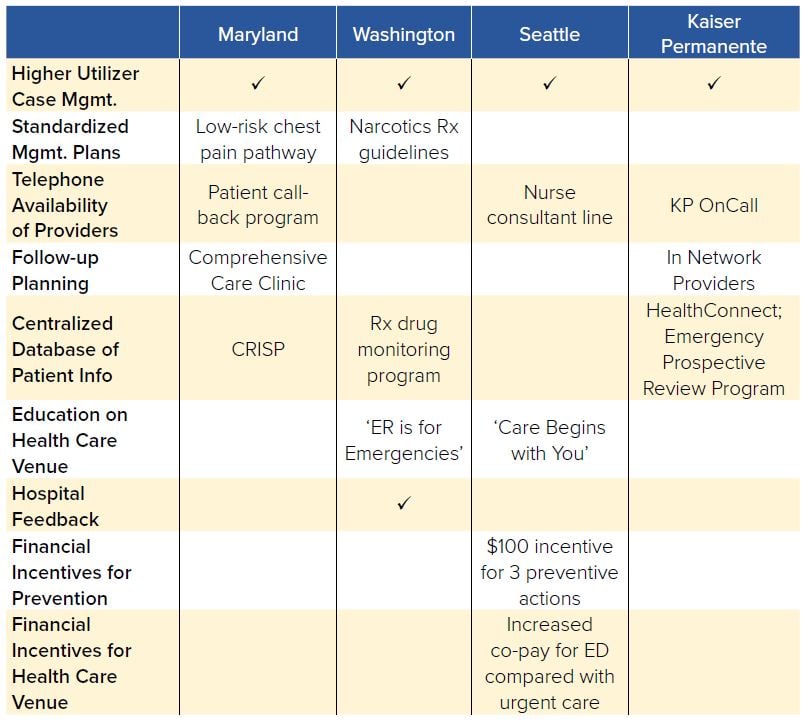

TABLE 7.1. Initiative to Improve ED Utilization

University of Maryland Upper Chesapeake Health (Chesapeake)

In 2010, Maryland implemented the Total Patient Revenue payment reform. Under this model, the 10 participating hospitals received fixed dollar payments to cover both inpatient and outpatient hospital-based care, independent of the current year’s volume. Given this fixed budget, hospitals were incentivized to increase efficiency and provide alternatives to unnecessary ED utilization. An analysis by the Brookings Institute in 2015 demonstrated that the alternative care plan programs resulted in a 40–50% reduction in hospital-based encounters in high-cost patients.25

Washington State’s “ER is for Emergencies” Program (Washington)

In 2012, Washington State Medicaid proposed reducing acute health care spending by limiting payment after three ED visits. Amid social and political backlash, the Washington chapter of ACEP, the Washington State Medical Association, and the Washington State Hospital Association offered the “ER is for Emergencies” program. This initiative sought to reduce Medicaid costs by decreasing unnecessary ED utilization and drug-seeking behavior. Though these interventions required significant initial financial investment, the Washington State Medicaid Program saved $34 million in its first year and saw a 10% decrease in ED visits.26

Seattle Group Health/SEIU Healthcare Effort (Seattle)

In a separate effort in the Seattle area, the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, a nonprofit entity that provides health care and health insurance, joined forces with the Service Employees International Union Healthcare NW Health Benefits Trust, which specifically serves home health care workers, to reduce ED use by targeting their most expensive beneficiaries. Of note, these 13,500 patients lived and worked in varying locations, were disproportionately middleaged, minority females with multiple comorbidities, and had primary languages other than English — a demographic whose behavior health policy experts consider exceptionally difficult to change. Despite this, the program reduced ED use among these patients by 27% over 4 years.27

Kaiser Permanente California (KP)

KP merges the finances of an insurance branch, a physician branch, and a facility branch, such that each branch shares the gains and subsidizes the losses of the other. Whereas in other markets these entities may be at odds with one another, this model demonstrates how coordination of efforts among all of those involved in health care delivery can improve patient outcomes and allow for shared savings. KP boasts a 40% lower ED utilization rate and a modest improvement in admission rate (13.2% vs 15.3%) when compared with the rest of the country.28

Common Themes Among Successful Solutions

Targeting ED utilization from a variety of angles, these programs achieved remarkably reduced acute care costs while still improving outcomes. First and foremost, they focus on prevention of acute health problems. Whether this means better management of chronic diseases, vaccinations against

preventable communicable diseases, or public health education, the bottom line is prevention. Secondly, they provide less expensive alternatives to ED care, such as rapid outpatient referral programs and urgent care centers. Lastly, they improve the efficiency of traditional ED workflows via better data systems such as EHR infrastructure.25

The unifying theme among all of these programs is the initiation of case management systems, which provide the trifecta of prevention, increasing use of alternative care venues, and improved ED efficiency.31,32 High utilizers are identified by case managers, after which a multidisciplinary team develops an individual care plan tailored to each patient’s needs. Standardized management plans for certain groups of patients have been shown to improve ED efficiency for common complaints of high utilizers. For instance, Chesapeake instituted a low-risk chest pain pathway that safely decreased chest pain admissions and increased utilization of outpatient risk stratification.25 Chesapeake integrates these plans into the EHR to make this information immediately available to treating providers.25 KP’s Emergency Prospective Review Program uses a call center staffed with KP emergency providers and nurses to coordinate the care of KP patients who also seek care at outside hospitals. KP also takes a slightly different stance on ED efficiency. Rather than focusing on ED throughput time, it allows providers to provide more comprehensive ED care. This is aimed at avoiding admission for studies that, if completed in the ED, could result in the discharge of an otherwise stable patient.28

Several systematic reviews note the success of case management programs in moderately reducing health care costs, but they show variable results for reducing the number of ED visits by adult high utilizers.29–31 Importantly, not all case management programs have demonstrated improved costs.30,32 Less successful programs may suffer from poor clinician buy-in of case management goals, lack of focused interventions, poorly defined financial goals, inexperienced case managers, or lack of incentive to reduce spending.33 The success of case management may hinge on its integration of preventive care with increased availability of alternate ED venues and streamlining the ED care of these patients.29

Increased provider availability to patients for advice on where to go and what to do about their acute health problems appears to decrease costs. Both Seattle and KP provide this service through call centers.26,28 Chesapeake made emergency care providers more available to patients and more involved in ensuring follow-up by offering payment for follow-up phone calls to at least 2 discharged patients per shift.25

While “appropriate” ED use is a slightly more controversial topic, both the Washington and Seattle programs implement educational campaigns to assist patients in choosing the health care setting most suited to their current health care needs. Seattle’s “Care Begins With You” program utilizes workers’ required recertification course as a venue for viewing an informational video aimed at educating patients regarding appropriate uses of the ED. Seattle’s program also financially incentivizes alternate care venue use through an increased co-pay for an ED visit of $200, while maintaining its urgent care copay at $15.26

Centralized databases of shared patient information seem to be another pillar of success when it comes to improved outcomes and decreased costs. Upper Chesapeake Health participates in the Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients (CRISP), which centralizes health information, such as previous ED visits and imaging results, for much of the Maryland and District of Columbia region. As a result of these interventions, opiate prescriptions and the overall cost of hospital-based encounters for traditionally high-cost patients have halved.25 KP’s EMR, HealthConnect®, similarly centralizes patient information from all participating hospitals; moreover, outside providers can access this resource through a dedicated call center. Improved access to patient history records permits more focused patient care, better patient interaction and avoids the risks and costs of duplicative testing among the many obvious benefits resulting from more information about the patient.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

High utilizers represent a challenge and opportunity for clinicians and policymakers. As research shows, high utilizers’ demographics are not always what society assumes. Afflicted by limited or poorly coordinated primary care, chronic and psychiatric diseases, and a variety of socioeconomic factors, high utilizers face an uphill battle in managing their health. However, there are many things providers and advocates can do to improve these patients’ outcomes:

- Take an extra minute to educate your patient on their health condition, proper follow-up, and appropriate ED use.

- Call primary care doctors to arrange outpatient work-ups or ensure follow-up of an acute condition.

- Partner with hospital social workers and case managers to devise high utilizer plans for the top users of your department.

- Educate your political representatives about the misconceptions regarding high utilizer demographics and the successful programs that have already demonstrated improved outcomes and costs.