Ch. 1 - Insurance Basics

Corey McNeilly, MA; Courtney Hutchins, MD, MPH; Elizabeth Davlantes, MD

In order to understand the present U.S. health insurance structure, it is important to understand its past. Health care policy has been shaped by American ideological values, those values heavily debated and ultimately resulting in controversial policies. By becoming familiar with our history, we can understand the possibilities for future policy and what it may take to get there.

Insurance coverage is the basis of access to care for many patients, but what is actually covered by their policy remains an area of constant concern.

Consider this timeline of major U.S. health policy in the past century.1

- In 1927 the Committee on Costs of Medical Care was established and began a 5-year study to examine the state of medical care in the country.

- In 1936 the Technical Committee on Medical Care was created to further study health status in the U.S. and examine the needs for health care and health insurance.

- In the 1940s, in the wake of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt called for an economic bill of rights, including “the right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health.” Not long after, Harry Truman proposed a comprehensive insurance program that was ultimately unpopular in the setting of anti-socialist sentiment at the time in the wake of WWII.

- Throughout the 1950s to the late 1960s, American ideology on health care became even narrower as the discussion began to shift from a need for comprehensive coverage for all, and health care as a right, to a solely economic issue.

- In 1965 the Medicare and Medicaid Act was passed to cover the elderly and those in poverty.

- In 1972 Social Security amendments pass, allowing people under age 65 with long-term disabilities and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) to qualify for Medicare coverage. Those with long-term disabilities must wait 2 years before qualifying for Medicare.

- From 1990–1994 President Bill Clinton worked on a universal health care proposal that included a “managed care” option and started a White House task force on health care reform. Ultimately, with opposition from organizations like the Health Insurance Association of American and a divided Congress, the proposal died.

- In 2006, Medicare Part D was passed while Massachusetts and Vermont passed comprehensive health care plans at the state level.

- In 2010 the House passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Medicare

After decades of debate over a national health insurance program to improve access for the elderly and those receiving public aid, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Medicare and Medicaid Act, specifically Title XVIII and XIX of the Social Security Act of 1965. Today, Medicare serves as the largest health insurance payer nationally. It covers more than 56 million Americans and had total expenditures of $678.7 billion in 2016.2

As the largest health insurance payer in the nation, Medicare is one of the most influential players in our nation’s health care system. Medicare sets national standards for hospital and physician reimbursement rates and funds a large portion of Graduate Medical Education. Medicare has also been a leader in pay for performance, quality standards, and national benchmarking initiatives that have reshaped health care in the past 20 years.

Funding for Medicare comes from tax contributions by employees and employers (known as payroll taxes), premiums and copays paid by beneficiaries, taxes on Social Security benefits, and a portion of national tax revenue from the general fund of the U.S. Treasury. However, recent

estimates project this trust will be depleted in 2026.3

Eligibility for Medicare includes Americans age 65 and older, individuals with disabilities, and individuals with ESRD. Coverage comprises 4 distinct parts:

- Part A covers hospital inpatient services and skilled nursing care.

- Part B covers outpatient, ED visits, and physician services.

- Part C “Medicare Advantage” is an optional managed care program that gives beneficiaries the option to enroll in Medicare benefits through private insurance coverage, which the government pays for in fixed premiums.

- Part D, added in 2006, covers prescription medications.

Prior to 1965, half of elderly Americans lacked health insurance; by 1970, 97% were covered. The number of Medicare beneficiaries will increase from 19 million in 1965 to an estimated 81 million by 2030. As the aging population continues to grow, along with the per enrollee health care costs, there will be continued pressure to provide quality coverage to this population at reduced costs.4 This has led to recurrent efforts by Medicare beneficiaries and large

lobby groups associated with them (eg, AARP) to defend included benefits, limit co-pays, and ensure access to services.

Medicaid

Medicaid arose alongside Medicare in 1965 with the goal of providing health insurance to the poor by supplementing existing entitlement programs.2

Medicaid now serves as the largest source of funding for medical and healthrelated services for America’s low-income population. It provides coverage for more than 76 million beneficiaries, including almost 33 million children and more than 10 million disabled Americans.5

CHIP

The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), also known as Title XXI of the Social Security Act, is part of the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997. The BBA provided $40 billion in federal funding to be used to provide health care coverage for low-income children living in households under 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) who do not qualify for Medicaid. States can elect additional coverage up to and beyond 300% of the FPL, but bear additional financial costs with reduced federal matching. The initial law only provided funding through 2007. However, CHIP has been reauthorized 3 times, with the most recent reauthorization in 2015 providing funding through fiscal year 2018.6 As of 2017, 9.4 million children were enrolled in the program. Since CHIP is a program within Medicaid, not a separate entity, it is also administered by individual states, federally regulated, and financed by both states and the federal government.7

Medicaid Administration

Medicaid differs from Medicare not only in its designated beneficiaries, but also in how it is run. Medicaid is administered by individual states and funded by each state with matching federal funds and subsidies. To receive funding from the federal government, states must meet national requirements. However, individual states largely set their own regulations and, until the passing of the ACA, their own eligibility criteria in relation to the FPL. For example, a 2-person household at 175% of the FPL may be eligible for Medicaid in one state but not in another.

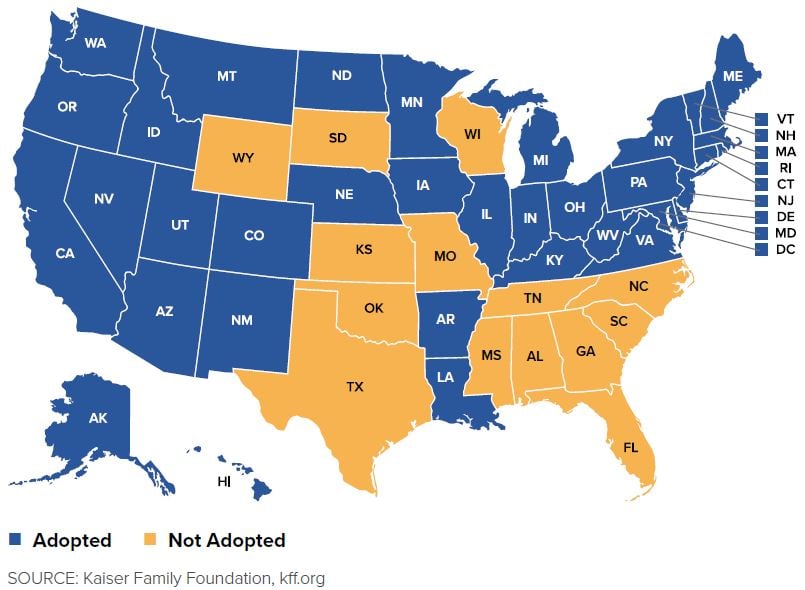

The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to all individuals under the age of 65 in households with income up to 138% of the FPL. This was designed to be expanded across the nation, standardizing Medicaid coverage and increasing access to coverage for millions of low-income Americans without insurance. As of February 2019, 37 states (including Washington, D.C.) had expanded Medicaid eligibility but 14 states had not.8

FIGURE 1.1. Status of State Expansion of Medicaid (as of February 2019)

Funding and Payment

In 2016, estimated “net outlays” for Medicaid were $581.8 billion.2 This included direct payment to providers of $266.4 billion, payments for premiums of $254.7 billion, payments to disproportionate share hospitals of $19.7 billion, and administrative costs of $28.1 billion. Additionally, $4.4

billion was spent for the Vaccines for Children Program under Title XIX. It is projected that with no other changes to the law, total outlays will reach $823 billion by FY 2022.2

Private Insurance Market

The private health insurance market functions by pooling risk across a large group of individuals and providing standardized coverage to the individuals that pay the premium. In the United States, private insurance can be purchased by an individual directly or through an exchange, although it is

more commonly provided by employers. Insurers cover most of the cost of beneficiaries’ preventive care and a portion of other health care expenses depending upon the type of coverage elected, deductible, and co-insurance requirements.

Wage control laws in World War II led to employer-based insurance programs marketed as “benefits” to recruit competitive candidates.9 These programs expanded after the war, growing in popularity because businesses could provide a form of tax-free compensation to employees. Expanding from initial coverage via fee for service, new and distinct models developed over the next 70 years to include various forms of capitation and copay.

The Exchanges

A major impetus for the development of the ACA was the lack of affordable insurance available to individuals. During the recession of 2008, this issue became more evident as individuals became part-time employees and lost their health benefits.10 Individuals faced high premiums and deductibles, limitations to the types of health care plans they could access, and discrimination against pre-existing health conditions. The ACA created thirdparty markets known as health insurance exchanges, which increased access to affordable coverage for individuals who did not have coverage through their employers. Approximately 10 million people were insured through the exchanges by June 2015.11 Current challenges include decreasing numbers of insurers in the marketplace, from an average of 6 insurers per state in 2015 to 3.5 insurers per state in 2018.12

The Affordable Care Act

The ACA (2010) was the most significant regulatory overhaul and expansion of health care coverage since the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. The ACA implemented many changes to expand access to health care coverage:13

- Individual Mandate Requirement: Most U.S. citizens and legal residents are required to have health insurance or pay a financial penalty.

- Exchanges: Creation of state-based American Health Benefit Exchanges for individuals to purchase coverage.

- Essential Benefits: New regulations on health plans available in the exchanges

- Medicaid Expansion: Medicaid coverage for all non-Medicare eligible individuals under the age of 65 with incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty level.14

Specific aspects of the ACA were challenged in a case that made its way to the Supreme Court in 2012.15 The Supreme Court ruled that the ACA’s requirement that certain individuals pay a financial penalty for not obtaining health insurance was authorized by Congress’s power to levy taxes.16 However, the court limited the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid. The Supreme Court ruled that Congress exceeded its constitutional authority by coercing states into participating in the expansion by threatening them with the loss of existing federal payments. This ruling afforded states the opportunity to decide individually if they would expand Medicaid in accordance with the ACA’s original guidelines. By the end of 2018, 34 states (including Washington, D.C.) had expanded Medicaid to cover more than 15 million individuals, but an estimated 2.2 million individuals remained uncovered who would be eligible under the expansion.17

The ACA has also faced extensive political pressure since its enactment. Congress, after coming under Republican control in 2010, passed multiple bills to repeal the ACA while President Barack Obama was in office, but all were vetoed. Under President Donald Trump, there has been an expansion of short-term health plans (also known as “skimpy” plans), the repeal of the individual mandate tax penalty, and a reduction in the enrollment time period and advertising. While not the full repeal and replace initially proposed, the potential impacts on the program remain significant.

Why the ACA’s Essential Health Benefits protection is of interest to the ED population

The ACA requires all health benefits plans to offer at minimum the essential health benefits package,18 including those offered through the exchanges and those offered in the individual and small group markets outside the exchanges. The essential health benefits package includes items and services in 10 benefit categories:

- Ambulatory patient services

- Emergency services

- Hospitalization

- Maternity and newborn care

- Mental health and substance use disorder services including behavioral health treatment

- Prescription drugs

- Rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices

- Laboratory services

- Preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

- Pediatric services, including oral and vision care

The ACA also requires that the scope of benefits be equal to that of a “typical employer plan” and that the benefits reflect an appropriate balance among the categories. These essential benefits and standards prevented the practice of increasingly skinny coverage being offered by some insurance companies as a way to fulfill coverage obligations at an attractive price point. This practice had left many patients surprised to find out how little was actually covered by catastrophic plans and the cost they faced when accessing even preventive care.

These essential health benefits are specifically relevant to emergency medicine because they require insurers to cover emergency department visits. The ACA requires all plans to cover behavioral health treatment, mental and behavioral health inpatient services, substance use disorder treatment, and pre-existing mental and behavioral health conditions. Furthermore, by mandating coverage of preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management, the ACA helps patients both with and at risk for chronic conditions that previously would only have been able to use the ED for their care.

Demographics and numbers of the remaining uninsured

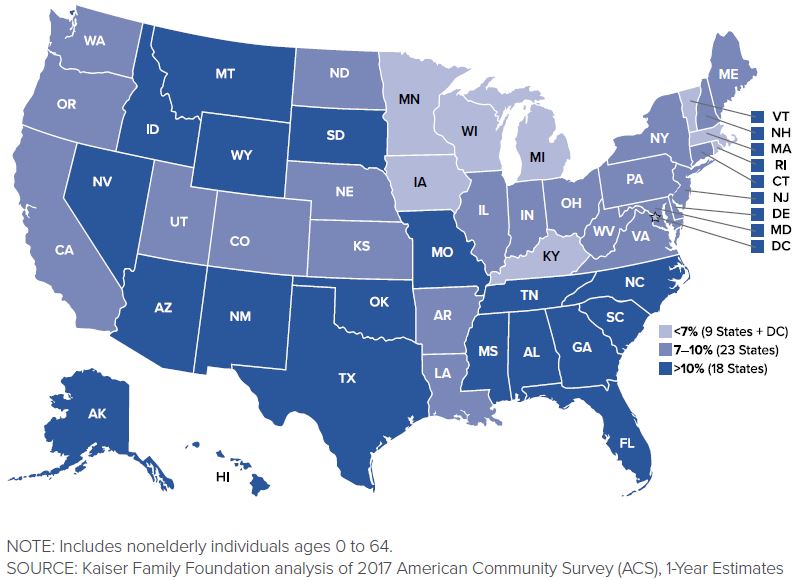

Under the ACA the number of uninsured nonelderly Americans decreased by 16 million between 2013–2016, from 44 million in 2013 to less than 28 million at the end of 2016.19 Among the 28 million individuals who remained uninsured, 45% still cited the high cost of insurance as the main reason for their lack of coverage.19

FIGURE 1.2. Uninsured Rates Among the Nonelderly by State, 201719

Despite the coverage increases from 2013 to 2016, individuals who remained without insurance were still mostly low-income adults since children have greater availability of public coverage in many states: 85% of the uninsured were nonelderly adults, while the uninsured rate among children was under 5%. Individuals at the highest risk of being uninsured were those below the poverty level, but 80% of uninsured families had incomes below 400% of the poverty level. Increased participation by states in the Medicaid expansion would provide additional coverage to many of these remaining uninsured populations.

Despite debate over reversing the ACA after the presidential election in 2016, millions of people gained coverage under the ACA provisions that went into effect in 2010. As of this publication, more than 27.6 million Americans remain uninsured because of cost, lack of individual state expansion, and several other reasons discussed in this chapter. What will be done about it in coming policy reform remains to be seen.19

WHAT’S THE ASK?

Insurance coverage is the basis for access to care for many patients, but what is actually covered by their policy remains an area of constant concern.

Advocacy on the basics of insurance includes:

- Knowing how to direct an uninsured patient to the exchange in your state.

- Appreciating if your state has participated in the ACA Medicaid Expansion.

- Understanding the Essential Health Benefits, their importance in having adequate coverage, and how they impact patients in the ED.