Ch. 6 - Non-Emergent Visits and Challenges to the Prudent Layperson Standard

Cameron Gettel, MD; Ramu Kharel, MD, MPH; Elizabeth A. Samuels, MD, MPH, MHS

In the 1980s and 1990s, private insurers frequently required prior authorization for emergency department visits. In the event of an emergency, patients were expected to contact their insurance carrier prior to going to the ED to request coverage for their visit. Those who did not were frequently denied coverage if their final diagnosis was deemed to be “nonurgent” or “non-emergent.”1 This practice led to fear about potentially devastating financial consequences of an ED visit and discouraged patients from visiting the ED even in the event of life-threatening emergencies.

The prudent layperson standard is vital to maintaining an environment of patient-centered care where patients can feel secure in seeking emergency care, without fear of reprisal if their final diagnosis is found to not be urgent or emergent.

In response, states began implementing the “prudent layperson” standard, beginning with Maryland in 1993.2 The prudent layperson standard defined an emergency medical condition as:

“…a medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that a prudent layperson, who possesses an average knowledge of health and medicine, could reasonably expect the absence of immediate medical attention to result in placing the health of the individual (or, with respect to a pregnant woman, the health of the woman or her unborn child) in serious jeopardy, serious impairment to bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part.”3

This standard required insurance companies to reimburse for emergency services when patients’ presenting symptoms met this definition of an emergency medical condition, regardless of their ultimate diagnosis. If the patient’s chest pain turned out to be only acid reflux and not a heart attack, the ED visit was still covered, since a prudent layperson could reasonably expect that chest pain requires immediate medical care. The standard was adopted by 33 states and later by Medicare and Medicaid (Managed Care Contracts) in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.4,5 In 1999, it was extended to all federal employees. ACEP campaigned to integrate the prudent layperson standard as a universal standard for ED visits and was ultimately successful in 2010 with the passage of the Affordable Care Act, which adopted the prudent layperson standard as the standard for emergency coverage for nearly all medical plans.6

“Non-Emergent” ED Visits

Under the prudent layperson standard, insured patients are protected and provided appropriate insurance coverage for ED care when they feel they are having a medical emergency. However, many insurers and policymakers still question the necessity of some emergency department visits.

While there continues to be contention surrounding the definitions of “nonurgent,” “inappropriate,” or “unnecessary” ED visits, these encounters are frequently cited as a cause of rising health care costs in the United States. Overall health care expenditures have increased from 7.9% of GDP in 1975 to 17.8% of GDP in 2015.7 Data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) suggests that emergency care accounts for around 4% of the total health care expenditure in the United States.8 The CDC defines a non-urgent visit as a medical condition requiring treatment within 2–24 hrs.9-12 Emergent requires care in less than 15 minutes, urgent requires care within 15–60 minutes, and semiurgent requires care within 1–2 hours.

In 2015, CDC found that out of 136.9 million ED visits that year, only 5.5% were considered non-urgent.9 Furthermore, the number of patients presenting to the ED for non-urgent complaints significantly declined during the previous decade, from 13% in 2003 to 5.5% in 2015.9

Despite the medical necessity of the vast majority of ED visits and the significant decline over the years in non-emergent visits, some insurance companies are denying payment if they consider the discharge diagnosis to be nonurgent or non-emergent. A landmark 2013 JAMA study evaluated a 2009 data set from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) of just under 35,000 ED patients and revealed that 6.3% had a “primary care treatable” discharge diagnosis. Of that subset, nearly 90% had similar presenting complaints compared to other patients needing ED evaluation, hospital admission, or immediate operative intervention, suggesting limited correspondence between presenting complaint and discharge diagnosis.13 This major overlap in the presenting symptoms between the urgent and non-urgent visits underscores the validity of the prudent layperson standard and the need for evaluation by a trained emergency medicine provider to identify life-threatening emergencies.

This work was supported and expanded upon by a more recent 2018 study that assessed ED patients subject to possible denial of coverage under the policy of Anthem Inc., a large national insurer. This cross-sectional analysis of 2011-2015 NHAMCS data assessed ED visits with a discharge diagnosis deemed to be nonemergent by Anthem. For those visits subject to denial, nearly 40% were initially triaged as urgent or emergent and 26% received 2 or more diagnostic tests.14 Unfortunately, the push to control costs for insurance companies will likely result in these policies continuing despite the lack of evidence.

Legislative Threats to the Prudent Layperson

In addition to insurance companies, many states are still pursuing reduction of ED visits to control growing health care costs. One particularly noteworthy example was enacted in Washington state. In 2011, the Washington State Healthcare Authority drew criticism for attempting to cut Medicaid spending by limiting reimbursement for ED visits to 3 visits per year for any condition deemed to be “non-urgent.” Contrary to the precedent set by the prudent layperson standard, the list of non-urgent complaints was based on final diagnosis rather than presenting symptoms. Additionally, the list of final diagnoses included such emergent medical conditions as chest pain, vaginal bleeding in pregnancy, and seizures.

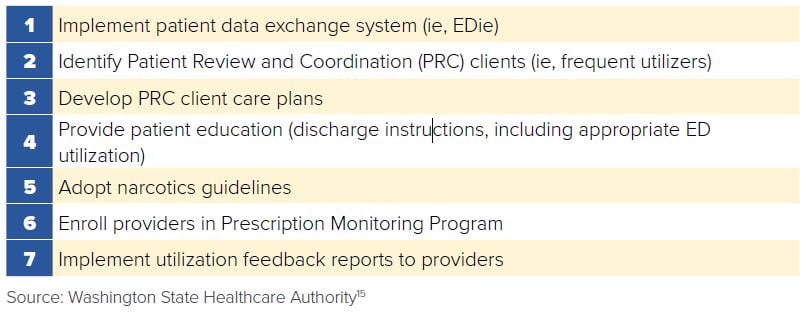

After fighting to block the regulation, Washington state’s ACEP chapter led the development of the “ER is for Emergencies” program, which aimed to reduce costs by identifying 7 best practices (Figure 6.1). These standards were implemented by all Washington hospitals and included patient education regarding appropriate ED use, development of care plans with coordinated case management for frequent users of EMS and EDs, implementation of narcotic prescribing guidelines, and the creation of a health information exchange, the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE). By sharing information in EDs across the state through the EDIE, this ACEP-led effort saved Washington State Medicaid $34 million in the first year of program implementation and decreased visits for controlled substances by 25%, all while protecting the rights and safety of patients established by the prudent layperson standard.15

FIGURE 6.1. Seven Best Practices

Other states have also faced challenges to the prudent layperson standard. In 2011, Kentucky Spirit, a managed care organization, attempted to institute a new policy declaring that it would only reimburse $50 for any ED visit in which the final diagnosis did not meet a predetermined list of emergency medical conditions.16 Similar legislation in Louisiana sought to pay hospitals and providers a $50 triage fee for ED visits for non-emergent conditions, rather than providing appropriate reimbursement for an ED visit, where the definition of non-emergent was based on a patient’s final diagnosis.17 In Pennsylvania, a 2014 draft of the Healthy Pennsylvania program proposed that part of determining an individual’s insurance premium would be based on “appropriate use of ER services” without specifying the criteria used to determine which visits are appropriate or how it would distinguish between emergent and non-emergent conditions.18 All of these programs are attempts to find ways to reduce coverage and costs for state Medicaid programs similar to the private sectors efforts.

Enactment of the ACA made the prudent layperson standard federal law and extended it to individual and small group health plans and to self-funded employer plans. Emergency physicians nationwide fear that attempts to repeal the ACA may strip the prudent layperson standard, potentially allowing insurance agencies to revert back to retroactively denying of coverage beyond the programs they are currently attempting to implement with the law in place.

Private Insurance Threats to Prudent Layperson

With wide variability cited in the rates of non-emergent and non-urgent ED visits, insurers have promulgated higher estimates in attempts to curb costs, suggesting they are overpaying for care that could be delivered outside of the ED in drugstore clinics, nurse advice hotlines, and through telemedicine.19

Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, one of the country’s largest health insurers with more than 40 million members, developed a policy to retroactively deny claims they deem to be “non-emergent.” The policy has been implemented in several states, and the insurance company plans on expanding it, asking patients to be able to determine the level of medical care they require and, if incorrect, be financially responsible for their decision despite lack of medical training. In Missouri, starting in 2017, Anthem BCBS implemented a policy that no longer covered ED visits deemed nonurgent, encompassing nearly 2,000 diagnoses.20 Anthem has been reluctant to release information regarding its policy development, prior denials, and if ED visits have been deterred.

Using a list of predetermined non-emergent ICD-10 codes, an Anthememployed medical director reviews ED claims, often without further patient medical record encounter information, to make decisions on coverage denial.21 ACEP has worked with local chapters and key congressional offices to pursue legislation in affected states to protect the prudent layperson standard. Under public pressure, Anthem conceded it will request and review medical records prior to denying claims, as well as adding “always pay” exceptions to the policy for when a patient received any kind of surgery, IV medication, MRI, CT scan, or if the ED visit was associated with an inpatient hospitalization.21 ACEP has also released videos for patients at www.FairCoverage.org outlining the dangers of the insurance giant’s controversial policy, while also encouraging patients and providers to contact state and federal legislators to maintain the prudent layperson standard.22

While Anthem was one of the first, the insurer is not alone in its desire to stop payment for services it retrospectively deems unnecessary. As a result of the ongoing threat to the prudent layperson and the ability of patients to seek needed care, ACEP in 2018 sued Anthem in Georgia in concert with the Medical Association of Georgia. The lawsuit argues that the Anthem Georgia policy violates the prudent layperson standard, and, furthermore, it violates the Civil Rights Act as its denials impact access to emergency medical care by members of protected classes.23

Given ongoing budget difficulties in many states, efforts to save health care dollars by limiting reimbursement for “non-emergent” ED visits are likely to continue. It is critical that emergency physicians are educated about the pitfalls

to this approach and also about evidence-based, effective, and safe strategies to contain health care costs and deliver cost-effective emergency care.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

EDs remain a vital part of the health care system, providing a safety net for millions of Americans. The prudent layperson standard is vital to maintaining an environment of patient-centered care where patients can feel secure in seeking emergency care, without fear of reprisal if their final diagnosis is found to not be urgent or emergent. Effective advocacy includes:

- Vigilantly tracking and opposing policies that threaten the prudent layperson legislative standard.

- Highlighting and confronting policies that use pre-established lists of discharge diagnoses or retrospective chart review to determine coverage retroactively.

- Helping dispel myths and inaccuracies about the need for and cost of emergency care.