Ch. 2 - Insurance Challenges

Eric Maughan, MD; Sahar Morkos El Hayek, MD; Jamie Akiva Kahn, MD, MBA

Receiving health care in America is often predicated upon insurance coverage. However, insurance companies and governments facing increasing costs, pressures to reduce premiums, and consumers who are confused about coverage has resulted in increasing challenges to coverage, to affordability, and to access.

Access to insurance does not guarantee affordable coverage or the ability to access care.

Challenges to Coverage

The American health care system is a patchwork of patients receiving insurance from different sources including employers, individually purchased, and from the government through Medicare (primarily for those over age 65) and Medicaid (primarily for low-income Americans). Recent policy changes, notably the ACA, impact all these sources and contribute to the system’s complexity and dynamism. These policies include a mandate that all large employers provide health insurance for their employees, a mandate that all individuals who do not get insurance through their employer purchase their own, and the expansion of Medicaid to more Americans. But this dynamic system continues to change, and the repeal of the individual mandate tax penalty and elimination of cost sharing reductions (CSR) are two of the more recent major policy changes that are projected to potentiate market instability, making insurance access and coverage more volatile.3

Repeal of the Individual Mandate (The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act 2017)

The ACA’s individual mandate required all Americans to obtain health insurance or pay a penalty tax of $695 or 2.5% of income, unless they qualified for an exemption.4 Many health economists agree that such a mandate is necessary because it creates a stable risk market and spreads health care costs among both healthy and sick, young and old. Without such a requirement, there is a concern that sicker (and more costly) patients could be disproportionately overrepresented in the market (adverse selection) and can lead to a collapse of the market (death spiral).

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act4 passed in December 2017 and to be implemented in 2019 repeals the tax penalty associated with the individual mandate. In the absence of tax penalty, the incentive to enroll may become obsolete for some populations, especially healthier and higher income members of society. This may translate into lower rates of enrollment of healthy patients and an increase in insurance premiums as the risk pool becomes sicker. Some studies project that eliminating the individual mandate will increase premiums by 7–15% by 2019,5 which could lead to millions of more Americans being uninsured.6 Some states are implementing their own version of the individual mandate, but this has not been a widespread effort and the effects are yet unknown.

Cost Sharing Reduction Elimination

The CSR is a discount associated with the ACA that lowers the out-of-pocket maximum deductible and copayments. After taking into account an individual’s income and health plan, an insurance company agrees to not charge above a certain amount to the patient and receives that lost revenue as a payment from the federal government. The legality of such federal payments has been debated in courts for years, and in 2017, President Trump’s administration decided to no longer make those payments. This created considerable market imbalance and uncertainty among insurers, who faced a higher-risk population, greater cost burden, and less confidence in the market. In most states, insurance companies compensated by increasing premiums (which are subsidized by the federal government as well), and many consumers chose to purchase other health plans. The Congressional Budget Office forecasts that eliminating the CSR will increase the federal deficit, but will not have a huge impact on the number of uninsured, as the higher premiums will be offset by higher tax credits for those premiums. However, they forecast that more companies will drop out of the insurance market, due to the political instability around the policy.7

Market Uncertainty and Decrease in Insurer Options

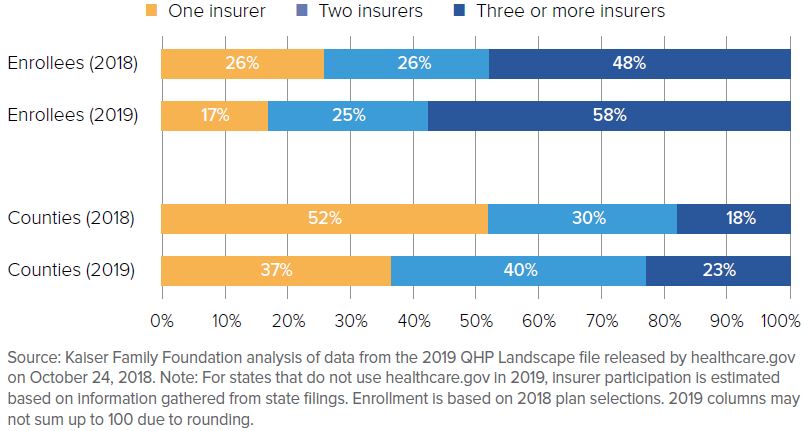

The substantial uncertainty in federal implementation of policies affecting insurance markets (eg, cost-sharing reduction payments, enforcement of the federal mandate) is complemented by inconsistent ACA Medicaid expansion across states. The ACA was designed so that low-income individuals would be covered by a more expansive Medicaid program while others would be covered by other reforms (including the employer mandate mentioned above). However, due to a Supreme Court decision, the option to expand Medicaid to cover all those intended by the ACA was left up to individual states. In 2018, 14 states had still not expanded Medicaid programs, leaving millions of uninsured adults outside the reach of the ACA with limited options for affordable health coverage.8 This unpredictable expansion pattern is affecting both payers and consumers. Insured citizens in non-expansion states are facing higher insurance premiums as insurance companies are slowly exiting the market to avoid suffering revenue cuts.9 Those companies that are staying risk uncertainty in predicting cost offsets.10 This trend holds across the country, as the political uncertainty around the ACA is hurting competition in the markets. In 2018, states averaged 3.5 insurers participating on their health insurance marketplaces, compared with an average of 5 insurers per state in 2014. The average number of plans per state dropped from 4.3 to 3.5 between 2017 and 2018, and the number of states with only one issuer rose from 5 in 2017 to 8 in 2018.11

FIGURE 2.1. Insurer Participation In ACA Marketplaces, 2018–201911

Challenges to Affordability

Some insured Americans are finding that access to insurance does not grant access to affordable health care, due to high deductible health plans (HDHPs), Medicaid restrictions, and new narrower health plans.

High Deductible Plans

HDHPs are increasingly common, covering nearly 40% of Americans with employer-based coverage in 2016 (up from 26% in 2011).12 Initially touted as a way to reduce health care costs, these plans have also decreased access to care for some Americans.

Much of the evidence behind HDHPs comes from the Rand Health Insurance Experiment (HIE) of the 1970-1980s. In that randomized controlled trial, nearly 3,000 families were assigned to coinsurance rates ranging from 0%–95%, with deductibles up to $3,000 (in 2018 dollars). Those patients who were randomized to a higher deductible plan spent up to 30% less on health care, with minor differences in health outcomes13 (limited to worse management of hypertension and vision in low-income patients). It is estimated that the widespread adoption of these plans has kept annual health care spending growth 0.9 percentage points lower than it would have been without HDHPs.14

While the rise of HDHPs decreased health care costs, it has harmed some patients as well. The Rand HIE showed worse health outcomes for those unable to afford their deductible. As 40% of Americans report not having $400 with which to easily cover an unexpected emergency expense, the average deductible now far exceeds the liquid savings of the average American and may result in reduced access to care.15 According to the CDC, 15.5% of patients with employer-based HDHPs had problems paying medical bills, compared with 10.3% in a traditional plan.16 Additionally, the cost savings of HDHPs are not generally from lower prices or from patients comparing prices for medical care, but from individuals receiving less care. Again, this matches the CDC’s data: 8.5% of those with HDHPs admitted forgoing medical care due to concern about cost, compared to 4.1% with a traditional plan.16 Whether this decrease in care leads to worse health outcomes has not been firmly established, but the decrease has been noted even in “highly effective” aspects of care, including preventive medicine.

Medicaid Restrictions

With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid has played an expanding role in access to health care in the U.S. However, access to Medicaid is decreasing in some states because of the choice to not expand Medicaid coverage, a requirement that Medicaid recipients contribute financially to their care and, most recently, a work requirement for Medicaid applicants. Medicaid work requirements, implemented by 4 states and considered by an additional 7 as of 2018, mandate that non-disabled Medicaid applicants spend 80 hours each month working, looking for work, volunteering, or involved in “community engagement.”17 Proponents of this requirement argue that by encouraging working and volunteering, Medicaid recipients will be healthier and the program will be able to focus on the vulnerable populations that it was originally designed to help: pregnant women, children, and people with disabilities.18 Opponents argue that health is needed for employment opportunities, that there is no evidence such restrictions with reduce costs or improve health, and that these will merely be a means to decrease health insurance coverage, harming other vulnerable populations. As these programs are in their infancy and face legal challenges before implementation, there will surely be more analysis and debate to come.

Skinny Health Plans

The Affordable Care Act established new requirements for insurance plans (the 10 Essential Benefits) across the country, including procedures and conditions to be covered and who can be refused coverage or charged a different premium. However, short-term health plans, designed for low-income, healthy workers or those between jobs and without access to employer-based insurance, are exempt from some of these restrictions. These plans were limited in duration to 90 days by President Obama in 2016,19 but President Donald Trump then expanded the duration to 12 months, renewable up to 36 months, effectively allowing these short-term plans to become long-term coverage.

Proponents of these plans suggest that by not being subject to the ACA requirements, these plans are less expensive than compliant plans, insuring those for whom the ACA plans are too expensive while increasing competition in the health insurance market.20 Opponents argue that these plans can saddle patients with unexpected medical bills, that they undermine the consumer protection inherent in the ACA, and that they may siphon healthier patients out of the ACA risk pool, leading to a collapse of the ACA insurance market. These plans are also just emerging in 2018, and more time and data are needed to determine their true effect.

Challenges to Access

Once patients have navigated the challenges getting covered for and affording medical care, they may still have challenges accessing care. These challenges come in many forms, including narrow networks and insurers’ reluctance to pay for some visits.

Narrow Networks

In order to better control costs, many insurance plans have a network of providers they require patients use resulting in patients having difficulty getting care if their preferred provider is not “in network.” This has been a problem since the rise of HMOs well before the ACA and has grown steadily worse. Of health plans on the Health Insurance Marketplace (set up by the ACA), 73% were considered narrow network in 2018, compared with 54% in 2015.21 The problem extends beyond the marketplace, as up to half of large employers began considering narrow network plans for their employees.22 Some providers (especially radiology, anesthesiology, pathology, and emergency medicine) may be out-of-network despite working at an in-network hospital, leading to surprise medical bills. Patients covered by these plans may also be unable to receive care at their preferred or most convenient location.

Of course, difficulty finding a doctor despite having insurance is not limited only to privately insured patients. According to the CDC, only 69% of doctors in 2018 were accepting new Medicaid patients, compared to nearly 85% accepting new Medicare or private insurance patients.23 Opponents of Medicaid expansion have pointed to this as evidence that expanding Medicaid may not be the most efficient way to provide care.

Prudent Layperson Standard

Another obstacle for insured patients trying to access care is that insurers in some states may refuse to pay bills for what they deem to be non-emergent ED visits. Currently, insurers are required to pay for ED visits based on the “prudent layperson standard” (if the symptoms could be considered by a person without medical training to be an emergency). This symptom-based model is being replaced in some instances with a retrospective, diagnosis-based model, which could leave some patients responsible for the bill of a visit that was determined retrospectively to be non-emergent. The challenges to the prudent layperson will be discussed more in Chapter 6.

WHAT’S THE ASK?

Access to insurance, does not guarantee affordable coverage or the ability to access care. Advocacy on the challenges of insurance include:

- Understanding the significance of new policies and their effect on insurance markets.

- Knowing the facts in your state. Has your state expanded Medicaid? What’s your state’s uninsured rate? How many insurers exist in the market? How are insurance premiums changing with policies?

- Educating your patients on their options to get insured and the difference between insurance, affordability, and coverage.